Introduction

This article includes a discussion of cerebral hypotonia, central hypotonia, essential hypotonia, benign congenital hypotonia, and floppy infant. The foregoing terms may include synonyms, similar disorders, variations in usage, and abbreviations.

Overview

Hypotonia is a clinical manifestation of numerous diseases affecting the central and/or peripheral motor nervous system. The key to accurate diagnosis involves integral steps of evaluation that include a detailed history, examination, and diagnostic tests. “Cerebral” (or central) hypotonia implies pathogenesis from abnormalities in the central nervous system, and related causal disorders include cerebral dysgenesis and genetic or metabolic disorders. Patients with central hypotonia generally have hypotonia without associated weakness, in contrast to the peripheral (lower motor neuron) causes, which typically produce both hypotonia and muscle weakness. Hypotonia is a clinical manifestation of over 500 genetic disorders; thus, a logical, stepwise approach to diagnosis is essential.

Key Points

- Hypotonia is reduced tension or resistance of a passive range of motion.

- The first step in the evaluation of a child with hypotonia is localization to the central (“cerebral”) or peripheral nervous system, or both.

- Central hypotonia is more likely to be noted axially with normal strength and hyperactive to normal deep tendon reflexes.

- Other clues to central hypotonia include dysmorphic facies, macro or microcephaly, developmental delay (global, motor, or cognitive), seizures, malformations of other organs, altered level of consciousness, abnormal eye movements, abnormal breathing pattern, or other signs of central nervous system dysfunction.

- A majority of diagnoses arise from history and physical exam, but neuroimaging, genetic testing and other laboratory evaluations are also important in diagnosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Presentation and Course

Hypotonia is an end product of multiple diseases affecting the upper and/or lower motor nervous system. Accurate diagnosis involves key steps of evaluation that include a detailed history, examination, and diagnostic tests.

Assessing a child with “hypotonia” typically takes place in the immediate postnatal period, in early infancy, or within the first 1 to 2 years of life. It may be readily apparent at birth or may be noted as a child fails to make normal developmental progress. Central hypotonia is more common, accounting for 60% to 80% of the presentation of hypotonia. Despite an extensive differential diagnosis list for central hypotonia, genetic and metabolic diagnoses have been reported to account for up to 60% of these cases.

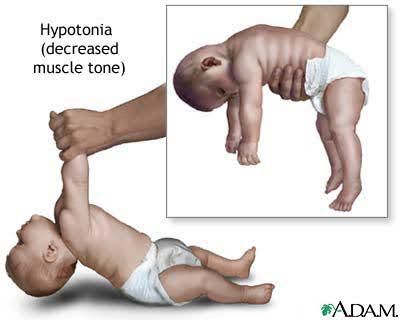

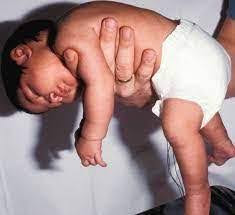

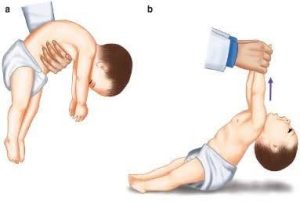

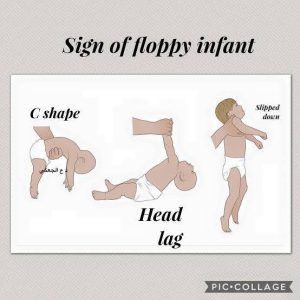

Clinical signs of low tone in infancy include hip abduction with legs externally rotated in the supine infant (“frog-leg posture”), arms extended at rest, head lags greater than expected for the age when arm traction applied, increased distance of arm pull with the anterior scarf sign, and low tone notes on both vertical (“slip through” at the shoulders) and horizontal (c-curve overhand) suspension. Central hypotonia is more typically axial in distribution, although infants with a significantly low tone may have a paucity of antigravity movements similar to a child with weakness and hypotonia. Muscle power (strength) and deep tendon reflexes are preserved in disorders with central hypotonia.

Source: Qais Saadoon, A. (2018). Essential Clinical Skills in Pediatrics. Springer.

Source: Peredo, D. E., & Hannibal, M. C. (2009). The floppy infant: evaluation of hypotonia. Pediatrics in review, 30(9), e66–e76. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.30-9-e66

Source: https://youtu.be/KfnJ9Hpu8dsTVMariel. (2014, September 2). 09/23. Clinical Pediatrics: Hypotonia 3 [Video]. YouTube.

Source: Biology Online. (2023, August 25). Hypotonic. https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/hypotonic

Low tone, however, may also present as a child ages with delayed motor milestones (along the spectrum of mildly delayed walking or impaired handwriting to significantly impaired milestones). Hypotonia can affect both gross and fine motor movements. Hypotonia may also manifest with oromotor symptoms, including poor feeding, drooling, swallowing problems, or speech difficulty. Abnormal posture can also pose difficulty in feeding, and joint laxity places the child at increased risk for dislocations or other skeletal abnormalities.

Other clinical signs used to support a diagnosis of central hypotonia include encephalopathy, global developmental delay, seizures, dysmorphic features or other organ structural abnormalities, visual or hearing impairment, and hyperreflexia.

Other clinical signs will vary by the specific diagnosis of each patient. However, these other symptoms are important in the algorithms for diagnosis. For example, central hypotonia associated with normal creatine kinase and global developmental delay leads down a different diagnostic pathway than hypotonia associated with weakness but no cognitive impairment.

Clinical History

When evaluating a patient with hypotonia, important questions to help elucidate the diagnosis would include:

Prenatal History

- Age of mother at time of birth: increased odds of chromosomal disorders with advanced maternal age.

- Nature of baby’s intrauterine movements: neuromuscular disorders may have decreased movements, or hypoxia may cause sudden change in movements.

- History of infections or teratogens during pregnancy: rhythmic movements in utero may represent intrauterine seizures and increased risk of cerebral abnormalities. TORCH infections and teratogens increase risk of cerebral abnormalities and hypotonia.

- History of polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios: maternal history of previous miscarriages and fetal demise. May represent inheritable metabolic or genetic conditions.

- Abnormalities on screening ultrasounds: congenital brain and other organ anomalies are more often linked to central causes of hypotonia, whereas arthrogryposis multiplex is often linked to peripheral/neuromuscular disorders.

- Presentation at birth: breech presentation is common in hypotonia and/or neuromuscular disorders.

- Positive family history of neuromuscular disorders, ie, myotonic dystrophy in the mother.

Birth/Perinatal History

- History of prematurity: increased risk for cerebral abnormality, complications, and cerebral palsy.

- Mode of delivery, complications/difficult birth: hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy may lead to CNS damage.

- Difficulties sucking/swallowing: may be seen with hypoxic-ischemic injury, cerebral palsy, cerebral disorders, and neuromuscular causes.

- Poor respiratory effort: may be seen with hypoxic-ischemic injury but, if not in context with the overall clinical picture, reflects possible neuromuscular cause.

- Encephalopathy: if out of context of birth history, may reflect underlying metabolic disorder or severe cerebral dysgenesis.

- Neonatal seizures: if out of context of birth history, may reflect underlying metabolic disorder or cerebral dysgenesis.

- Unexplained metabolic “lab” abnormalities: consider metabolic disturbances and inborn errors of metabolism.

Developmental History

- Moderate to severe developmental delay and retardation: genetic, cerebral dysgenesis.

- Normal previous development and loss of previously acquired motor skills: consider muscular dystrophies, progressive/intermittent metabolic disorders, or neurodegenerative disorders.

- Mild delay in motor development with normal IQ and social development: “benign hypotonia” or normal variation in development.

Medical History

- Seizure disorders: cerebral dysgenesis, genetic, metabolic, chromosomal disorders.

- Learning disabilities and behavioral disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder reflect overall abnormality of brain development often associated with mild hypotonia.

- Recurrent respiratory infections: neuromuscular dysfunction, possible central dysfunction.

- Detailed review of systems: determine other associated malformations or systemic involvement.

Pertinent Exam Findings

- Vital sign disturbance: may reflect severe cerebral dysgenesis, neuropathy, effects from hypoxia, or acute illness.

- General dysmorphic features point to a possible genetic abnormality.

- Skin: neurocutaneous abnormalities may reflect underlying genetic syndrome (neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis).

- Ocular exam: retinal findings, “cherry red spot,” optic nerve exam (atrophy, pale disc) may reflect underlying metabolic abnormality. Abnormal optic nerve may indicate “central causes,” Septo-optic dysplasias, etc.

- Hepatosplenomegaly: TORCH infections, glycogen storage diseases, inborn errors of metabolism.

- Extremities: abnormal digits, etc., may be characteristic of genetic syndromes.

- Other organ abnormalities (cardiovascular, genitourinary): genetic syndromes or associations.

Neurologic Exam

- Head circumference:

- Microcephaly: more common in central causes such as TORCH infections and genetic syndromes.

- Macrocephaly: neurocutaneous genetic syndromes, possible CNS disturbance such as hydrocephalus.

- Mental status: normal IQ points to neuromuscular causes.

- Nystagmus, erratic eye movements, strabismus: more common in central causes.

- Prominent facial weakness: congenital myopathies, myasthenia gravis. Possible brainstem effects from hypoxia or cerebral dysgenesis. “Hypotonic facies” typically describe a child with an open, downturned mouth and eyelid lag (secondary to hypotonia of facial muscles).

- Other dysfunctions of cranial nerves (ie, Mobius syndrome, hearing loss): more likely central causes, genetic causes.

Motor System Evaluation

- General observation:

- Resting position: Frog-leg position indicates significant hypotonia, especially in neonates when baseline tone is flexor. “W” sitting in an older child is indicative of proximal hypotonia.

- Muscle atrophy or fasciculations: more common in neuromuscular disorders.

- Extent of movement: hypotonia is often associated with a lack of spontaneous movement.

- Distribution of movement: In certain conditions, such as anterior horn disease, there may be only movement of the distal extremities. Wide-based gait and genu recurvatum are also indicative of hypotonia.

- Ventral suspension: an infant is typically held in ventral suspension, in which the infant is supported by a hand under the chest. Head control, trunk curvature, and movement of the extremities can be readily assessed. A normal newborn will hold the head about 45 degrees or less to the horizontal, the back will be straight or only slightly flexed, the arms flexed at the elbows and partially extended at the shoulder, and the knees partially flexed. An infant with hypotonia may look like a “rag doll” and slump forward and need more support. An infant with a possible central cause of hypotonia may scissor in ventral suspension.

Source: Farkas, V. (n.d.). Psychomotor development mental retardation. Semmewlweis University. http://www.gyer2.sote.hu/okt/ea/psychomotorFV111108.pdf

- Traction of the hands in the supine position will typically result in some degree of flexion in full-term and premature infants, but a hypotonic infant may have prominent head lag.

- Muscle strength may be more difficult to assess. One method to gauge movement is the ability of the neonate to sustain the posture of a limb against gravity. In older children, strength may be more easily tested.

- Reflexes: more typically diminished or absent in neuromuscular disorders; likely to be increased in central disorders.

- Sensory disturbance: may reflect nutritional causes, neuropathies, patterns of abnormalities suggestive of central causes (previous stroke, etc.).

- Coordination: a hypotonic patient may be more uncoordinated from muscle tone abnormalities, but frank ataxia would make one consider more prominently cerebellar disorders or central causes.

Prognosis and complications

The prognosis of centrally-based hypotonia may be significantly different based on the etiologic process. For cases of children with cerebral dysgenesis, the symptoms of hypotonia are often not as disabling as the other developmental problems that may accompany the disorder, such as static encephalopathy and intellectual disability.

A hypotonic patient may be at risk for musculoskeletal problems such as contractures, joint dislocation, respiratory compromise, and orthopedic complications based on abnormal postures and positions.

Hope this helps!

Gayane Zakaryan

Head of Rehabilitation Services

<<ArBes>>